A set is a collection that lets you quickly find an existing element. However, to look up an element, you need to have an exact copy of the element to find. That isn’t a very common lookup—usually, you have some key information, and you want to look up the associated element. The map data structure serves that purpose. A map stores key/value pairs. You can find a value if you provide the key. For example, you may store a table of employee records, where the keys are the employee IDs and the values are Employee objects. In the following sections, you will learn how to work with maps.

1. Basic Map Operations

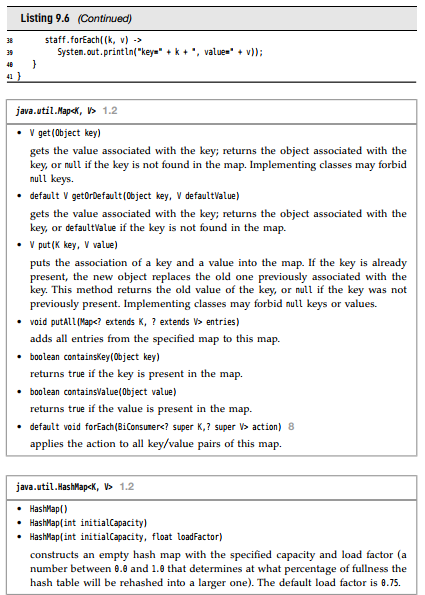

The Java library supplies two general-purpose implementations for maps: HashMap and TreeMap. Both classes implement the Map interface.

A hash map hashes the keys, and a tree map uses an ordering on the keys to organize them in a search tree. The hash or comparison function is applied only to the keys. The values associated with the keys are not hashed or compared.

Should you choose a hash map or a tree map? As with sets, hashing is usually a bit faster, and it is the preferred choice if you don’t need to visit the keys in sorted order.

Here is how you set up a hash map for storing employees:

var staff = new HashMap<String, Employee>(); // HashMap implements Map

var harry = new Employee(“Harry Hacker”);

staff.put(“987-98-9996”, harry);

…

Whenever you add an object to a map, you must supply a key as well. In our case, the key is a string, and the corresponding value is an Employee object.

To retrieve an object, you must use (and, therefore, remember) the key.

var id = “987-98-9996”;

Employee e = staff.get(id); // gets harry

If no information is stored in the map with the particular key specified, get returns null.

The null return value can be inconvenient. Sometimes, you have a good default that can be used for keys that are not present in the map. Then use the getOrDefault method.

Map<String, Integer> scores = . . .;

int score = scores.getOrDefault(id, 0); // gets 0 if the id is not present

Keys must be unique. You cannot store two values with the same key. If you call the put method twice with the same key, the second value replaces the first one. In fact, put returns the previous value associated with its key parameter.

The remove method removes an element with a given key from the map. The size method returns the number of entries in the map.

The easiest way of iterating over the keys and values of a map is the forEach method. Provide a lambda expression that receives a key and a value. That expression is invoked for each map entry in turn.

scores.forEach((k, v) ->

System.out.println(“key=” + k + “, value=” + v));

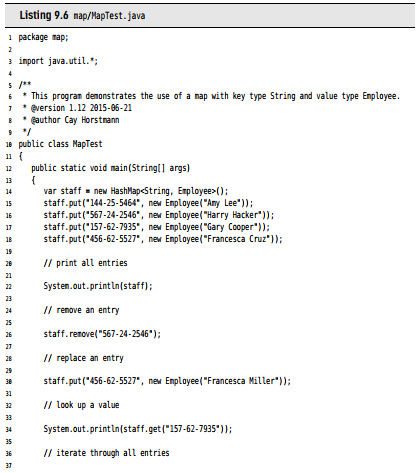

Listing 9.6 illustrates a map at work. We first add key/value pairs to a map. Then, we remove one key from the map, which removes its associated value as well. Next, we change the value that is associated with a key and call the get method to look up a value. Finally, we iterate through the entry set.

2. Updating Map Entries

A tricky part of dealing with maps is updating an entry. Normally, you get the old value associated with a key, update it, and put back the updated value. But you have to worry about the special case of the first occurrence of a key. Consider using a map for counting how often a word occurs in a file. When we see a word, we’d like to increment a counter like this:

counts.put(word, counts.get(word) + 1);

That works, except in the case when word is encountered for the first time. Then get returns null, and a NullPointerException occurs.

A simple remedy is to use the getOrDefault method:

counts.put(word, counts.getOrDefault(word, 0) + 1);

Another approach is to first call the putIfAbsent method. It only puts a value if the key was previously absent (or mapped to null).

counts.putIfAbsent(word, 0);

counts.put(word, counts.get(word) + 1); // now we know that get will succeed

But you can do better than that. The merge method simplifies this common operation. The call

counts.merge(word, 1, Integer::sum);

associates word with 1 if the key wasn’t previously present, and otherwise combines the previous value and 1, using the Integer::sum function.

The API notes describe other methods for updating map entries that are less commonly used.

3. Map Views

The collections framework does not consider a map itself as a collection. (Other frameworks for data structures consider a map as a collection of key/value pairs, or as a collection of values indexed by the keys.) However, you can obtain views of the map—objects that implement the Collection interface or one of its subinterfaces.

There are three views: the set of keys, the collection of values (which is not a set), and the set of key/value pairs. The keys and key/value pairs form a set because there can be only one copy of a key in a map. The methods

Set<K> keySet()

Collection<V> values()

Set<Map.Entry<K, V>> entrySet()

return these three views. (The elements of the entry set are objects of a class implementing the Map.Entry interface.)

Note that the keySet is not a HashSet or TreeSet, but an object of some other class that implements the Set interface. The Set interface extends the Collection interface. Therefore, you can use a keySet as you would use any collection.

For example, you can enumerate all keys of a map:

Set<String> keys = map.keySet();

for (String key : keys)

{

do something with key

}

If you want to look at both keys and values, you can avoid value lookups by enumerating the entries. Use the following code skeleton:

for (Map.Entry<String, Employee> entry : staff.entrySet())

{

String k = entry.getKey();

Employee v = entry.getValue();

do something with k, v

}

If you invoke the remove method of the iterator on the key set view, you actually remove the key and its associated value from the map. However, you cannot add an element to the key set view. It makes no sense to add a key without also adding a value. If you try to invoke the add method, it throws an UnsupportedOperationException. The entry set view has the same restriction, even though it would make conceptual sense to add a new key/value pair.

4. Weak Hash Maps

The collection class library has several map classes for specialized needs that we briefly discuss in this and the following sections.

The WeakHashMap class was designed to solve an interesting problem. What happens with a value whose key is no longer used anywhere in your program? Suppose the last reference to a key has gone away. Then, there is no longer any way to refer to the value object. But, as no part of the program has the key any more, the key/value pair cannot be removed from the map. Why can’t the garbage collector remove it? Isn’t it the job of the garbage collector to remove unused objects?

Unfortunately, it isn’t quite so simple. The garbage collector traces live objects. As long as the map object is live, all buckets in it are live and won’t be reclaimed. Thus, your program should take care to remove unused values from long-lived maps. Or, you can use a WeakHashMap instead. This data structure cooperates with the garbage collector to remove key/value pairs when the only reference to the key is the one from the hash table entry.

Here are the inner workings of this mechanism. The WeakHashMap uses weak references to hold keys. A WeakReference object holds a reference to another object—in our case, a hash table key. Objects of this type are treated in a special way by the garbage collector. Normally, if the garbage collector finds that a particular object has no references to it, it simply reclaims the object. However, if the object is reachable only by a WeakReference, the garbage collector still reclaims the object, but places the weak reference that led to it into a queue. The operations of the WeakHashMap periodically check that queue for newly arrived weak references. The arrival of a weak reference in the queue signifies that the key was no longer used by anyone and has been collected. The WeakHashMap then removes the associated entry.

5. Linked Hash Sets and Maps

The LinkedHashSet and LinkedHashMap classes remember in which order you inserted items. That way, you can avoid the seemingly random order of items in a hash table. As entries are inserted into the table, they are joined in a doubly linked list (see Figure 9.11).

For example, consider the following map insertions from Listing 9.6:

var staff = new LinkedHashMap<String, Emptoyee>();

staff.put(“144-25-5464”, new Emptoyee(“Amy Lee”));

staff.put(“567-24-2546”, new Emptoyee(“Harry Hacker”));

staff.put(“157-62-7935”, new Emptoyee(“Gary Cooper”));

staff.put(“456-62-5527”, new Emptoyee(“Francesca Cruz”));

Then, staff.keySet().iterator() enumerates the keys in this order:

144-25-5464

567-24-2546

157-62-7935

456-62-5527

and staff.values().iterator() enumerates the values in this order:

Amy Lee

Harry Hacker

Gary Cooper

Francesca Cruz

A linked hash map can alternatively use access order, not insertion order, to iterate through the map entries. Every time you call get or put, the affected entry is removed from its current position and placed at the end of the linked list of entries. (Only the position in the linked list of entries is affected, not the hash table bucket. An entry always stays in the bucket that corresponds to the hash code of the key.) To construct such a hash map, call

LinkedHashMap<K, V>(initialCapacity, loadFactor, true)

Access order is useful for implementing a “least recently used” discipline for a cache. For example, you may want to keep frequently accessed entries in memory and read less frequently accessed objects from a database. When you don’t find an entry in the table, and the table is already pretty full, you can get an iterator into the table and remove the first few elements that it enumerates. Those entries were the least recently used ones.

You can even automate that process. Form a subclass of LinkedHashMap and override the method

protected boolean removeEldestEntry(Map.Entry<K, V> eldest)

Adding a new entry then causes the eldest entry to be removed whenever your method returns true. For example, the following cache is kept at a size of at most 100 elements:

var cache = new LinkedHashMap<K, V>(128, 0.75F, true)

{

protected boolean removeEldestEntry(Map.Entry<K, V> eldest)

{

return size() > 100;

}

};

Alternatively, you can consider the eldest entry to decide whether to remove it. For example, you may want to check a time stamp stored with the entry.

6. Enumeration Sets and Maps

The EnumSet is an efficient set implementation with elements that belong to an enumerated type. Since an enumerated type has a finite number of instances, the EnumSet is internally implemented simply as a sequence of bits. A bit is turned on if the corresponding value is present in the set.

The EnumSet class has no public constructors. Use a static factory method to construct the set:

enum Weekday { MONDAY, TUESDAY, WEDNESDAY, THURSDAY, FRIDAY, SATURDAY, SUNDAY };

EnumSet<Weekday> always = EnumSet.allOf(Weekday.class);

EnumSet<Weekday> never = EnumSet.noneOf(Weekday.class);

EnumSet<Weekday> workday = EnumSet.range(Weekday.MONDAY, Weekday.FRIDAY);

EnumSet<Weekday> mwf = EnumSet.of(Weekday.MONDAY, Weekday.WEDNESDAY, Weekday.FRIDAY);

You can use the usual methods of the Set interface to modify an EnumSet.

An EnumMap is a map with keys that belong to an enumerated type. It is simply and efficiently implemented as an array of values. You need to specify the key type in the constructor:

var personInCharge = new EnumMap<Weekday, Employee>(Weekday.class);

7. Identity Hash Maps

The IdentityHashMap has a quite specialized purpose. Here, the hash values for the keys should not be computed by the hashCode method but by the System.identityHashCode method. That’s the method that Object.hashCode uses to compute a hash code from the object’s memory address. Also, for comparison of objects, the IdentityHashMap uses ==, not equals.

In other words, different key objects are considered distinct even if they have equal contents. This class is useful for implementing object traversal algorithms, such as object serialization, in which you want to keep track of which objects have already been traversed.

Source: Horstmann Cay S. (2019), Core Java. Volume I – Fundamentals, Pearson; 11th edition.