Variables hold the data that your program manipulates while it runs, such as user information that you’ve loaded from a database or entries that have been typed into an HTML form. In PHP, variables are denoted by a $ followed by the variable’s name. To assign a value to a variable, use an equals sign (=). This is known as the assignment operator.

Here are a few examples:

$plates = 5;

$dinner = ‘Beef Chow-Fun’;

$cost_of_dinner = 8.95;

$cost_of_lunch = $cost_of_dinner;

Assignment works with here documents as well:

$page_header = <<<HTML_HEADER <html>

<head><title>Menu</title></head>

<body bgcolor=”#fffed9″>

<h1>Dinner</h1>

HTML_HEADER;

$page_footer = <<<HTML_FOOTER

</body>

</html>

HTML_FOOTER;

Variable names may only include:

- Uppercase or lowercase Basic Latin letters (A-Z and a-z)

- Digits (0-9)

- Underscore (_)

- Any non-Basic Latin character

, if you’re using a character encoding such as UTF-8 for your program file

, if you’re using a character encoding such as UTF-8 for your program file

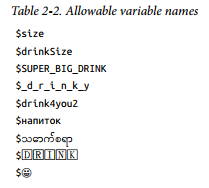

Additionally, the first character of a variable name is not allowed to be a digit. Table 2-2 lists some allowable variable names.

Keep in mind that, despite the alluring aesthetic possibilities of variable names with emoticons in them, most PHP code sticks with digits, underscores, and Basic Latin letters.

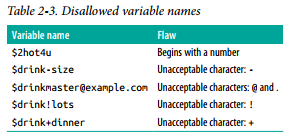

Table 2-3 lists some disallowed variable names and what’s wrong with them.

Variable names are case-sensitive. This means that variables named $dinner, $Dinner, and $DINNER are separate and distinct, with no more in common than if they were named $breakfast, $lunch, and $supper. In practice, you should avoid using variable names that differ only by letter case. They make programs difficult to read and debug.

1. Operating on Variables

Arithmetic and string operators work on variables containing numbers or strings just like they do on literal numbers or strings. Example 2-17 shows some math and string operations at work on variables.

Example 2-17. Operating on variables

$price = 3.95;

$tax_rate = 0.08;

$tax_amount = $price * $tax_rate;

$total_cost = $price + $tax_amount;

$username = ‘james’;

$domain = ‘@example.com’;

$email_address = $username . $domain;

print ‘The tax is ‘ . $tax_amount;

print “\n”; // this prints a line break

print ‘The total cost is ‘ .$total_cost;

print “\n”; // this prints a line break

print $email_address;

Example 2-17 prints:

The tax is 0.316

The total cost is 4.266

james@example.com

The assignment operator can be combined with arithmetic and string operators for a concise way to modify a value. An operator followed by the equals sign means “apply this operator to the variable” Example 2-18 shows two identical ways to add 3 to $price.

Example 2-18. Combined assignment and addition

// Add 3 the regular way

$price = $price + 3;

// Add 3 with the combined operator

$price += 3;

Combining the assignment operator with the string concatenation operator appends a value to a string. Example 2-19 shows two identical ways to add a suffix to a string. The advantage of the combined operators is that they are more concise.

Example 2-19. Combined assignment and concatenation

$username = ‘james’;

$domain = ‘@exampte.com’;

// Concatenate $domain to the end of $username the regular way

$username = $username . $domain;

// Concatenate with the combined operator

$username .= $domain;

Incrementing and decrementing variables by 1 are so common that these operations have their own operators. The ++ operator adds 1 to a variable, and the — operator subtracts 1. These operators are usually used in for() loops, which are detailed in Chapter 3. But you can use them on any variable holding a number, as shown in Example 2-20.

Example 2-20. Incrementing and decrementing

// Add 1 to $birthday

$birthday = $birthday + 1;

// Add another 1 to

$birthday ++$birthday;

// Subtract 1 from $years_left

$years_teft = $years_teft – 1;

// Subtract another 1 from $years_left

–$years_teft;

2. Putting Variables Inside Strings

Frequently, you print the values of variables combined with other text, such as when you display an HTML table with calculated values in the cells or a user profile page that shows a particular user’s information in a standardized HTML template. Double-quoted strings and here documents have a property that makes this easy: you can interpolate variables into them. This means that if the string contains a variable name, the variable name is replaced by the value of the variable. In Example 2-21, the value of $email is interpolated into the printed string.

Example 2-21. Variable interpolation

$email = ‘jacob@example.com’;

print “Send replies to: $email”;

Example 2-21 prints:

Send replies to: jacob@example.com

Here documents are especially useful for interpolating many variables into a long block of HTML, as shown in Example 2-22.

Example 2-22. Interpolating in a here document

$page_title = ‘Menu’;

$meat = ‘pork’;

$vegetable = ‘bean sprout’;

print <<<MENU

<html>

<head><title>$page_title</title></head>

<body>

<ul>

<li> Barbecued $meat <li> Sliced $meat

<li> Braised $meat with $vegetable </ul>

</body>

</html>

MENU;

Example 2-22 prints:

<html>

<head><title>Menu</title></head>

<body>

<ul>

<li> Barbecued pork

<li> Sliced pork

<li> Braised pork with bean sprout

</ul>

</body>

</html>

When you interpolate a variable into a string in a place where the PHP engine could be confused about the variable name, surround the variable with curly braces to remove the confusion. Example 2-23 needs curly braces so that $preparation is interpolated properly.

Example 2-23. Interpolating with curly braces

$preparation = ‘Braise’;

$meat = ‘Beef’;

print “{$preparation}d $meat with Vegetables”;

Example 2-23 prints:

Braised Beef with Vegetables

Without the curly braces, the print statement in Example 2-23 would be print “$preparationd $meat with Vegetables”;. In that statement, it looks like the variable to interpolate is named $preparationd. The curly braces are necessary to indicate where the variable name stops and the literal string begins. The curly brace syntax is also useful for interpolating more complicated expressions and array values, discussed in Chapter 4.

Source: Sklar David (2020), Learning PHP: A Gentle Introduction to the Web’s Most Popular Language, O’Reilly Media; 1st edition.